How The Internet Changed Fangirling Forever

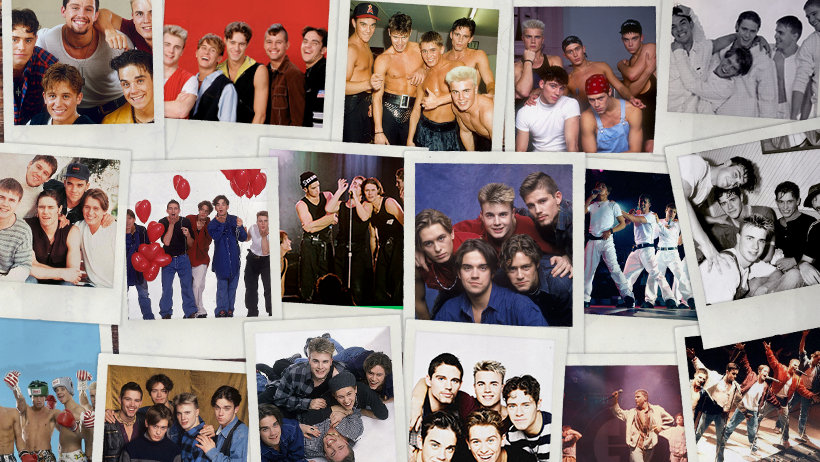

It’s hard to overestimate the impact of the internet on, well, everything. One of those things is fangirling. While we female music fans have been around for decades, the internet has been vital in our emancipation and has changed how we are perceived by wider society. Somewhere in pre-internet times, I was 13 and became a fan of ‘the biggest and best British boy band of the 90s’ (as I call them), Take That. My experience back then left me fascinated with just how agitated people get about girls who like pop bands. I’m committed to spreading the word that fandom is not a superficial, silly thing, but something important and empowering. Read on for a trip back in time, and find out how fangirl life was changed forever when we all got online.

Fangirl Life: Obsessed

My first encounter with Take That was seeing the video for It Only Takes a Minute on MTV in 1992 (look it up for vintage Eurodance vibes and some epic breakdancing in a boxing ring). I was instantly fascinated and started cutting out pictures from magazines and glueing them into a scrapbook. At first, they had to share the pages with other celebrities I liked, like Kirk Cameron, Joey Lawrence (does anyone still know who these guys are?) and the cast of Beverly Hills 90210, but it soon became clear that I needed a dedicated Take That scrapbook. By the end of the 90s, I think I had about 7 or 8 books filled up. I also remember sticking their faces all over my diary and scribbling their lyrics on everything. When I was first able to use our home internet connection to download stuff, around 1996, it felt so exciting to simply type in a keyword and have a bunch of tiny, pixelated images pop up. And what did I do with those images? I printed them out, made them into DIY sleeves for my mixtape cassettes, or stuck them in my scrapbooks.

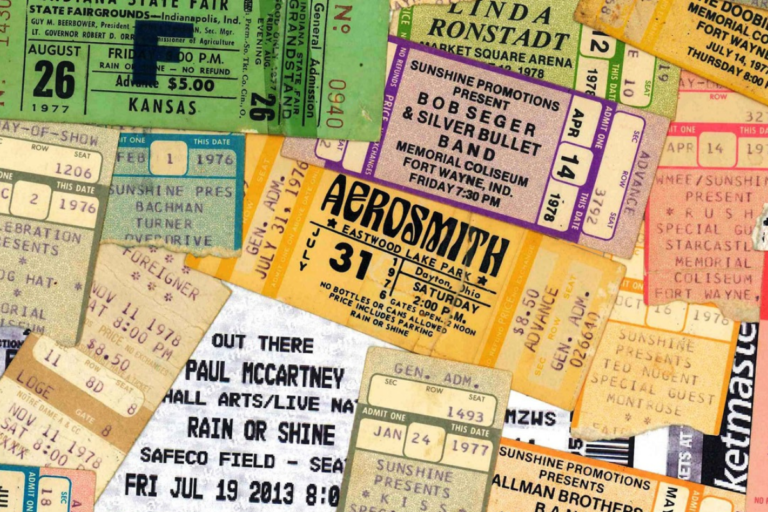

To be able to listen to Take That’s music whenever I wanted to, I had to go and purchase the CDs in an actual record store and suffer the shaming inflicted on me by the jaded, middle-aged guys who worked there. Anxiety-inducing for sure. But it was all worth it to be able to pull the plastic wrapper off a brand-new cd, put it in the player and listen to the whole album for the first time while devouring the booklet front to back.

As our family tv picked up a few international channels, I could watch things like Top of the Pops and BBC children’s Saturday morning tv, which is where all the pop acts would go to promote their singles. Take That would hang out during a 3-hour show, and in between cartoons perform their songs, answer questions from kids in the audience, and participate in random comedy sketches. It was honestly amazing. And if I couldn’t be home at the time of a certain tv appearance, I could program the VCR to tape it! Oh, the joy of coming back from vacation and having 3 or 4 tapings lined up. But I guess the UK and Germany were about as far as our TV antenna could reach, so there were a lot of appearances in other countries that I missed. To this day I‘ll find videos on YouTube from places like Denmark or Japan that I’ve never seen before.

My main news sources for all things pop music and Take That were radio, tv and teen magazines. Which was ok as long as I stayed home, where I had access to those things. I did not find out that Robbie Williams had left the band (in July 1995) until maybe weeks after the fact, because I happened to be on holiday in Italy at the time. I caught a glimpse of the front of BRAVO magazine in a shop and was left to reel from the shock while continuing on a hike with my family. My sister and I later coped with our emotions by cutting Robbie’s face out of the posters we had brought from home to hang on the walls of our holiday apartment.

Listening to music while travelling was a challenge in itself. You had to bring your cassette tapes and/or CDs with you, and hope there would be a stereo deck at your destination. Before I got a Discman, I would press my ear to a bright yellow cassette radio with one speaker, which was just small enough to fit in our luggage. But privacy to listen to your music? Not an option.

Of course, the internet has changed all of that. Streaming has made music more accessible, both financially and practically. Bring your phone and earbuds and you can listen to your favourite songs any time, any place. You can buy as many limited edition albums, t-shirts and mugs as your income allows, from the comfort and anonymity of your own home.

There’s an insane amount of artist content available online now. Appearances, interviews and concerts from all over the world are recorded and shared via Twitter, Tumblr, TikTok and any other platform you can think of. On top of that, there is fan-made content which has become a massive part of fan culture. And saving it all is as simple as making a screengrab or pressing the download button, with almost limitless storage space on devices or in the cloud. Following the latest updates and stories has become non-stop, 24/7. Social media, YouTube or Google alerts would all make a member leaving your favourite boy band extremely hard to miss.

Fan Culture: Others like you

I’m from Amsterdam in the Netherlands. Take That were definitely successful there, but it wasn’t like every girl was a fan of them like I had experienced in the 80s with, for example, an artist like Madonna. At my school, I was the lone defender of the faith. Or at least it felt that way! I had converted my sister, but except for her, I didn’t personally know any other Take That fans. In the mid-90s it was considered cool to listen to grunge music, Britpop or hip hop, and it was decidedly uncool to like a boy band. I was regularly shamed and laughed at by classmates, teachers and complete strangers. I did not yet understand that calling girls crazy or silly for liking something with a passion is rooted in patriarchy and reeks of misogyny, nor did I have the vocabulary to stand up for myself. So I let it get to me, and became a closet fan for a very long time.

Besides not wanting to show my fangirl-ness in public, I was also super shy, and my sister and I weren’t brave enough to go stand in front of hotels or show up at tv studios. (My parents probably wouldn’t have let us anyway, but that’s another story.) Not being able to latch on to a group of braver, bolder girls I already knew was definitely something that held me back from taking the leap and getting to hang out with others like us.

I only ever saw other Take That fans on tv or when we saw the band live, which I got to experience just twice in the 90s. Although I had theoretically known they existed, it was surreal to walk into an arena full of girls like me! Feeling the power of them screaming and singing so unabashedly was an absolute thrill. My mother was there with us and would complain about the ringing in her ears for years to come. She had also accompanied me and my sister to the record shop to queue for tickets on the morning they were released. Although I remember being super nervous that they would sell out before we got to the front of the line, that stress was nothing compared to the absolute hell that is buying tickets online!

I have no photos or videos of the concerts I went to because cameras were not allowed. Even if you did sneak one in, the quality was so much worse than any standard phone will give you nowadays. Sometimes, professional photographers would hand out flyers at shows letting you order prints of photos they had taken. By the late 90s, online fan forums had arrived. I remember finding a girl on there who had somehow managed to videotape a Gary Barlow solo concert that I had also been to. She sent me a copy of the tape in the mail, along with a note and some magazine clippings, and I just thought it was the sweetest thing ever.

Those forums were the start of fangirl culture as we know it now. Even if you literally have no one in your life who shares your obsession, you can go online and make like-minded friends there. It’s not as lonely now, being a fangirl. The online space provides ample examples of girls who speak out and are proud to be a fan. The knowledge that there’s more of you, that you are not crazy, is freeing and emboldening. There is strength in numbers.

In addition, the internet has made fandom more democratic. Anyone can start conversations and share their opinions and thoughts. Expressions of creativity around fandom sometimes become the start of a career: music artists posting fan covers on YouTube have been signed by record labels, creators of social media fan accounts have found jobs in marketing, and works of fan fiction have been published and turned into films. Fandom has also become more global. It is now a lot easier to discover bands that are not well known in your own country and become part of a community that covers the globe. Fangirls arrange real-world meetups to share experiences, organise themselves in activism, or just have fun chatting about their faves for hours.

Parasocial Relationships: Getting to know them

Music artists used to feel much more distant and unattainable than they do now. There was a big split between ‘pop stars’ and ‘regular people’, and more of a mystery as to what these magical creatures were actually like behind the scenes. An exception to this would be the early fans ‘from before they were famous’. I know that the members of Take That knew a lot of their fans by face and name when they started out, and I’ve seen videos of them kissing girls on the lips at performances and signings. Imagine that!

But I, like the vast majority of their fans, did not know what the Take That boys were doing unless they were appearing, at that moment, on live television. I had no idea what their family members looked like, or what they got up to in their spare time. At the height of their fame, we got Take That Official, a fan club magazine that I could buy at WH Smiths, a British retailer that had a store in Amsterdam. It contained interviews, behind-the-scenes reports, fan letters and of course lots of posters. Take That also released a number of VHS tapes which included their music videos plus hilarious banter and short features on each member, similar to One Direction’s This Is Us or BTS’s BANGTANTV videos. The magazine and the videotapes were ways for us fans to connect with them semi-directly, and feel like we were getting to know them on a more intimate level.

But if you wanted to speak to your idol directly for more than a few frantic seconds at an airport, Meet and Greet competitions were the only way. Usually organised by radio stations, Take That actually did a lot of these. Of course, I never won. Later, at the onset of the internet, Gary started to show up in chat rooms to talk to fans, but there was no way to be sure it was really him. I believed it was though, and I still have the paper printouts of entire chats from that period.

Now, artists have blue checks behind their names and share snippets of their lives on social media. This makes them seem more approachable and closer to us regular folk. You can send direct messages if they follow you back, making communication a two-way street. There’s less of a gap between the artist and the fan. Some fangirls have become extremely proficient at tracking where band members are at any given time, having developed advanced online investigative skills and ways of sharing that information with lightning speed.

Then there’s the phenomenon of boy bands as a collaborative project. For example, the massive success of One Direction would never have been possible without fans getting behind the band from the very start. Directioners literally willed them into being, pushing them to stardom by spreading the word online, before their first single was even out. And in the case of BTS, band members work in parallel with ARMY for causes like social justice and mental health— causes deemed important by the fans.

Artists are able to react to issues in real-time and offer support, giving a greater sense of being there for their fans. In 2017, two weeks after the deadly bombing at an Ariana Grande show in Manchester, I was travelling to see a Take That show in London. Three days prior, terrorists had slammed their van into pedestrians on London Bridge and proceeded to stab people sitting in restaurants. Take That were very aware of the apprehension among their fans at that time. Gary was tweeting multiple times a day— asking how we were feeling, trying to calm our nerves and assuring us that everything would be done to keep us safe. I felt very supported by that and got a sense of my idols living in the same world as I was, managing similar challenges and fears. I felt the same way throughout the lockdowns during the pandemic. Gary, Mark, Howard and Robbie all did extra stuff online to keep us positive and entertaining, and it really made that time easier to get through for me.

Fan Labour: Making an impact

Traditionally, the main way fangirls have helped to propel their idols to success was by 1. showing up in droves for them, and 2. buying all the things. Sales numbers of albums, singles, concert tickets and merchandise, as well as the size of the crowd waiting at a tv studio or airport, were the main indicators of a boyband’s level of fame. Thanks to the internet, fangirls now play an even bigger role in the success of their idols. Instead of music and other content being offered to the masses to simply consume, fans now share their insights and opinions through social media and help shape the type of content that is created around an artist or band.

Starting with the development of the MP3 format and the founding of Napster in the late 90s, the music industry has been adapting to circumstances that are radically different from what they were 25 years ago. As general music sales went down in the 00s and 10s, selling merchandise and tour tickets as well as monetizing YouTube views became increasingly important to an artist’s revenue. And it just so happens that fangirls play a huge part in all of those things.

Since the turn of the millennium, cd sales have dropped steeply. Revenue from streaming however has grown exponentially since 2010. It has now almost completely replaced the purchase of physical albums and singles among teens, although vinyl holds on to a strong niche market. Aware of these statistics, fangirls have made active efforts to positively influence their idol’s chart positions through initiatives like streaming parties. And there are other ways for them to have an impact, too. In 2015, many Directioners were unhappy with the choice of singles from the album FOUR and felt it deserved more exposure. So, they started an online campaign around the hashtag #ProjectNoControl, in which they promoted the album track No Control as if it was an official single. This global effort got the song played on the radio, added to One Direction’s tour setlist and performed on tv in the US. No Control also became the first ever non-single to win a Teen Choice Award.

Music marketing teams have started to depend on the enthusiasm of fangirls to create buzz online and basically do their work for them. Memes gone viral and trending hashtags can give marketing campaigns a big boost, so record companies will encourage fans to share updates, vote for their favourites and join in discussions on public platforms. All that fan-generated content is free promotion for their artists. News media has picked up on it as well, and fan campaigns and trending topics are now reported on all the time. Fan culture has become newsworthy in and of itself. How many times have you read an article that’s made up solely of fans’ tweets reacting to a certain pop culture event?

In Conclusion

From Lisztomania in the 1840s and Beatlemania in the 1960s to Stan Culture in the 2010s— girls have been excited by cute boys who make music for a long time. And although technology has evolved, the basic elements of fangirling have changed surprisingly little. Also since the beginning, female teenage fans of pop music have been called hysterical, uneducated and silly. I am happy to see that the increased outspokenness and visibility of fangirls in the past decade or so has started to positively impact how they are viewed by others, although there will always be people who choose to hang on to that outdated narrative. In any case, the fangirl community now has a much stronger position in society than it did when I was growing up.

And it’s all thanks to getting online! The internet has democratised and globalised fan participation, making music and related content widely accessible. The gap between idols and fans has gotten smaller, and many newer bands have more of a collaborative relationship with their audience. Fangirls no longer have to believe the patriarchal portrayal of themselves as crazy or of the music they love as worthless. They see themselves reflected in the many girls online who are powerful and have confidence in what they like. Because of fangirls’ importance for the music industry and their ability to organize themselves and make an actual impact, they are increasingly seen as a force to be reckoned with. There is a shift happening in the perception of fangirls: from passive, non-discerning consumers to self-aware and active creators.

Although I am now a bona fide grownup with kids and work and everything, I have never stopped being a passionate fan of pop music. And I was lucky because my boy band made a comeback! Take That has chaperoned me not only through my teenage years but through my adult life as well. Each of their songs represents a specific memory, taking me back to who I am at my core. I have come to see being a fangirl as a feminist act and have let go of the shame imposed on me as a teen. Watching younger generations embrace their fandom and do exactly what they feel like without explaining themselves or apologising, is extremely inspiring to me. I’m excited about the future of fangirling!

Annemarie Schumacher is the creator of Ode to Fangirls, an art project exploring all the ways it is feminist and fun to scream at a boy band with your friends. You can follow her work and join the conversation on Instagram @ode.to.fangirls