A Gallery of Ghosts: Halsey’s The Great Impersonator Honors the Icons and Identities She’s Inhabited

We’ve seen many iterations of Halsey across their career.

She appeared on the music scene as a mermaid-blue-haired 20-year-old, rising to popularity in the age of Tumblr-core and alt-pop with Room 93 and Badlands. She became a household name thanks to the mass success of Closer in 2016. She became the subject of unnecessary tabloid scrutiny for her relationships and open criticism of the music industry, as reflected in Manic. She battled health challenges for years, and became a mother and a business owner.

She’s been a chameleon, morphing in the public eye for a decade and hiding their heaviest moments from the outside world.

Then everything came crashing down when she received a life-threatening medical diagnosis. Faced with their own mortality, Halsey channelled fear, regret, and remembrance for the life she’s lived in the most brutally therapeutic way she could – creating an album, The Great Impersonator. Released on 25 October, the album simultaneously feels like a memorialisation for each iteration of themselves and like a gut-wrenching, uncertain homage to each life that has influenced theirs. Multidimensional, ever-fluxing, and utterly defenceless, The Great Impersonator is an incredibly executed, tangibly existential ultimatum in album form. It’s heavy, it’s honest, and it’s laced with the fragility of living with the uncertainty of your own mortality.

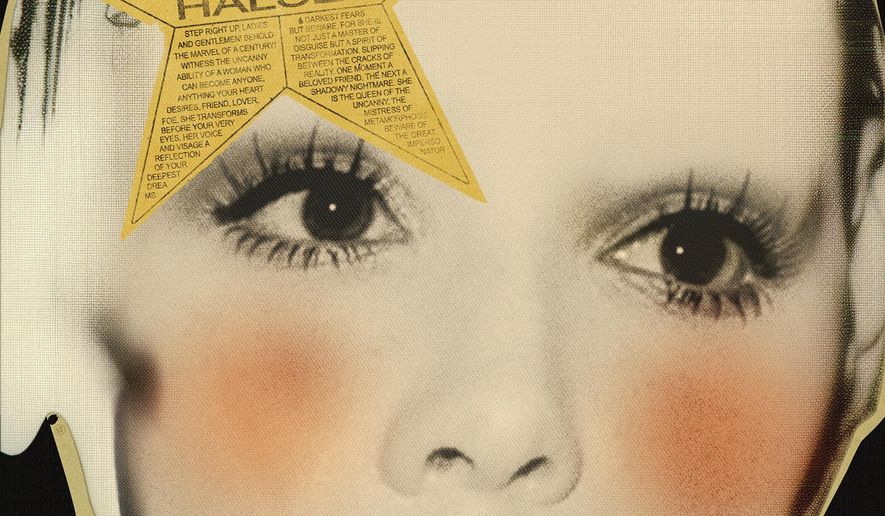

Perhaps the most impressive thing about The Great Impersonator is its dedication to recognizing how powerful music is as an art form. The album roll-out has been coupled with photographic impersonations of some of the most recognizable figures from Rumours-era Stevie Nicks and Toxic Britney Spears, to Marilyn Monroe and Bruce Springsteen paired with every single track on the album. The vinyl records were designed with interchangeable face inserts so variant collectors could intermix Halsey bodies and faces – or leave the face blank and just display a mirror insert. There isn’t a single song written for radio play, there’s been no promo tour – there have only been last-minute pop-up performances in intimate venues where Halsey can make the best connection with those who have respected her as an artist after the music industry chewed her up and spit her out.

Strangely enough, the album opener Only Girl in LA feels like a conclusive summary of The Great Impersonator rather than an introduction. Flipping pages through Halsey’s past and stripping away their identity along the way, she battles between sinking into contempt for a life in the spotlight and drowning in anonymity: “Well, I’m the only girl alive in L.A. County/I’ve never known a day of peace/I wake up every day and wish that I was different/I look around and it’s just me.” A sprawling six minutes and fourteen seconds in length and bursting at the lyrical seams, this soft-rock track breaks the expectations for what we know as a Halsey Album from the very beginning.

Halsey’s identity morphs and blurs with those of their sonic inspirations across the project, with certain tracks like I Believe in Magic and The End emerging as perhaps the most revealing moments on the record as she gets vulnerable about motherhood and medical battles. Other tracks like Lonely is the Muse and Lucky become so sonically intertwined as impersonations of Evanescence and Britney Spears respectively that their narratives about abandonment and exploitation deceive the more passive of listeners. This is the trick of The Great Impersonator – it gives glimpses into Halsey’s personal battles without giving concrete answers about anything.

There are artistic nuances across the album as well; Halsey’s son appears in the backing track of I Believe in Magic, offering a glimpse into the little joys in their life together. But it’s paired with the haunting reappearance of that child’s voice in the final of three Letter[s] to God (1998) where she cries out, “And I dont ever wanna leave him, but I dont think its my choice/So, I’m basking in these moments where I feel a shred of joy.” The three Letter to God tracks are a trove to unpack on their own, varying widely in genre and execution, but with each connecting on the shared lyric “Please, God/I dont wanna be sick/But I don’t wanna hurt so get it over with quick.”

The B-side of the album takes the hurt from the A-side and turns it darker, more melancholy. The Arsonist is laced with tarnishing abandonment while Life of the Spider (Draft) is so heavy with regret for an uncertain future that it cant even make it out of draft form – but this lends a vulnerability to the performance that wouldnt otherwise be palpable on the album. Life of the Spider (Draft) walks a fine line between heartbreaking and terrifying, as Halseys raw vocal soars through lines like “Im nothing but legs, they used to say/Im nothing but skin and bones these days/You dangle me high over the drain and tell me I’m lucky you don’t drop me there” and “I’m the shadow on the tile/I came for shelter from the cold/And I’d thought I’d stay a while I’m only small, I’m only weak/And you jump at the sight of me/You’ll kill me when I least expect it God, how could I even think of daring to exist?”

The back half of the album undeniably holds some of the most ambitious, most agonizing music of Halsey’s discography: I Never Loved You is simple but brutal, Darwinism is crushingly existential, and the title track itself closes the album with Halsey exposing every exploitative detail of her story. As she signs off, she poses one last question, letting her final word be this: “Does the story die with its narrator?”